The Trump Administration’s Response to COVID-19

With the recent resurgence in coronavirus cases, the Trump administration is being vilified by Democrats and the media (and some Republicans) for mishandling the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s too early to write a full and fair history of our nation’s response to the pandemic. But if you step back and review the administration’s actions, they responded responsibly and energetically, and they got quite a few things right, including:

- Halting direct air travel from China on January 31. (Unfortunately, we didn’t know enough to stop travel from Europe at the same time, which would have helped NYC.)

- Declaring a public health emergency at the end of January and a national emergency in mid-March, and activating the Defense Production Act, which helped the government work with private companies to combat the virus

- Prompting Treasury and the Fed to take swift action to create substantial liquidity, keep financial markets functioning, and avoid a credit freeze

- Promoting a policy of ‘flattening the curve’ to keep hospitals from being overwhelmed and buy time to develop new treatments and a vaccine. While New York hospitals were very full at the height of the first wave of cases in NYC, they were not overwhelmed like hospitals in Northern Italy.

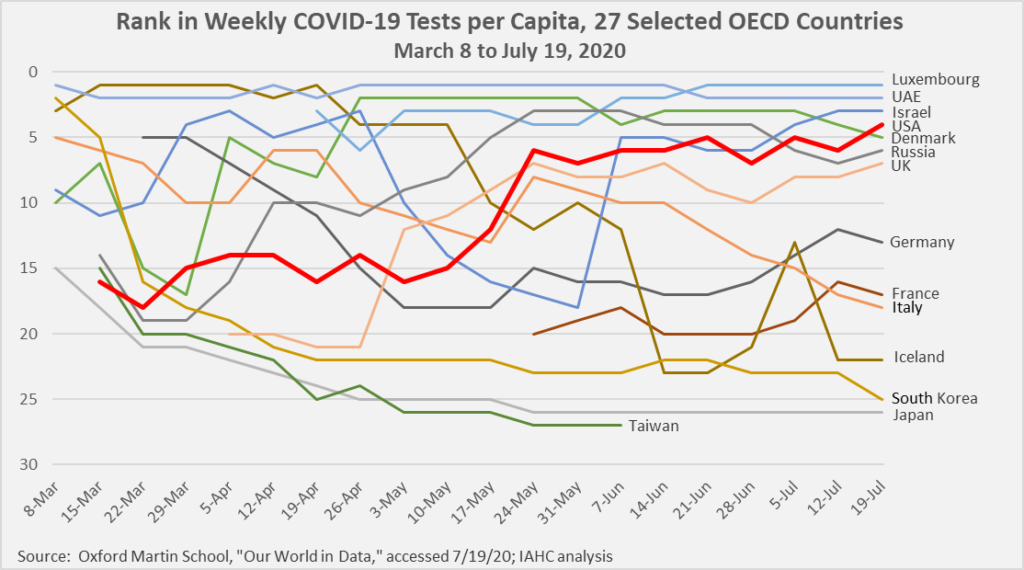

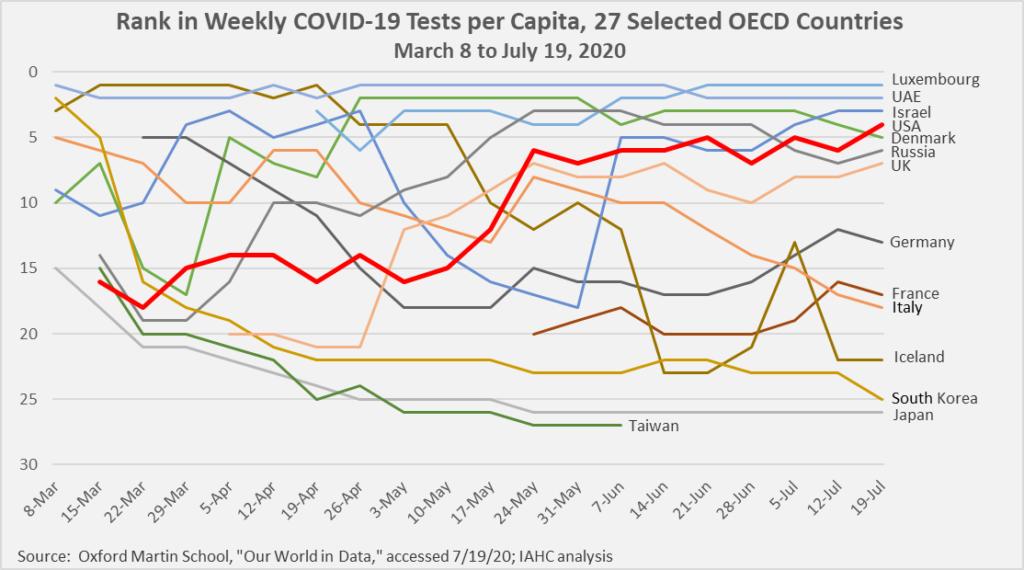

- Expanding COVID testing dramatically (after a slow start). The following chart shows total weekly tests per capita for the U.S. and 26 other OECD countries. The only countries that are testing more than we are now on a per capita basis are Luxembourg, the UAE, and Israel. Of course, we need to be testing a lot more, because we’ve got a bigger problem, which shows up in our high positive %.

- Negotiating and signing the CARES Act in March, which provided $2 trillion in relief to individuals, businesses, hospitals and public health departments, federal safety net institutions, state and local governments, and education. The Act isn’t perfect, and execution has been bumpy, but doling out $2 trillion in a fair and politically acceptable way is not an easy task.

- Organizing the rapid mobilization and distribution of essential equipment and supplies to early hot spots (especially NYC, which needed them, and Los Angeles, which didn’t). As with several actions, this started out bumpy, but both Governors Cuomo and Newsom ended up praising the President for his response to their requests.

- Organizing a massive public-private effort to produce PPE, ventilators, testing equipment, and materials, and launching “warp speed” efforts to develop therapies and vaccines to reduce the severity of the virus. (Unfortunately, tests, supplies, and vaccines are difficult to expand quickly and safely with current technologies.)

Beyond these federal initiatives, the administration has been encouraging governors to guide their states in ways they think best, consistent with our federated system. Above all, the administration has been trying to balance the devastating effects of the virus on mortality and morbidity with the devastating effects of shutting down the economy, which many people believe will end up harming more citizens than COVID-19.

Challenges

In evaluating the administration’s response, especially in comparison with other countries, one must keep in mind the many challenges this pandemic poses for our country:

- We are still learning about COVID-19. There are lots of things we don’t know, and our understanding is evolving. Dr. Fauci recently said that he’s never seen an infectious disease with such diverse effects. The interaction of the virus and patients’ immune systems is difficult to predict, except for people with compromised immune systems, who are very vulnerable. Many of the possible disease progressions are quite dangerous (e.g., cytokine storms). As a result, practitioners “in the trenches” are experimenting with different treatment protocols in a MASH-like environment. They don’t have time to wait for randomized controlled trials to save people’s lives.

The case of hydroxychloroquine provides a good example. Early research in France on the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine prompted some physicians to prescribe this drug before it was extensively tested in COVID-19 patients. President Trump famously announced he was taking it prophylactically, which painted a large target on it. While some early research suggested it did more harm than good, this research was flawed, and hydroxychloroquine now has a couple of peer-reviewed studies supporting its efficacy in certain doses at certain stages of the disease.

- We have the most diverse and mobile society in the world, making us a perfect target for a pandemic. Miami may have been infected by New Yorkers. The recent resurgence in Arizona, Texas, and Southern California appears partly linked with flows of people across our porous border with Mexico. We could never pull up the drawbridge like Taiwan or New Zealand to keep COVID out. It was already here and spreading rapidly before we knew what we were dealing with.

- Many states have underfunded their public health systems for years. While the CDC is the federal entity charged with protecting the country from health, safety and security threats, responsibility for developing and implementing public health policies and programs, including responding to epidemics, is delegated to the states. Unfortunately, many states do not have robust public health infrastructures, and the rapid growth of Medicaid has displaced spending on public health over time. Our state-by-state diversity may be better than a single large underfunded health system like Great Britain’s National Health Service, since some states can help others out. But, it’s not a lot better.

- We have a purposefully limited government that is constrained by our Constitution (especially the Bill of Rights) and our laws. While state governments have emergency powers they can use to protect their citizens, they are limited in scope and time, and they must be applied fairly. For example, limiting the right of assembly for religious congregations but not for civil demonstrations has been questioned by some courts.

Politics and the pandemic

The problem with making an honest assessment of the Trump Administration’s pandemic response can be summed up in one word – politics. This fall’s presidential election has given everyone, except undecided voters, a vested interest in celebrating or disparaging our response. Everyone has a conflict of interest. Democrats start with a bias toward finding fault simply because it is the Trump administration that is making the decisions, and they can’t say anything positive about a Trump-led initiative.

But the conflict is deeper than this. The trajectory of the virus and the U.S. economy over the next couple of months will almost certainly determine the outcome of the presidential race. This makes COVID-19 a natural ally of the Democratic party. The longer the virus persists and the longer the recession lasts, the greater the chance that Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic candidate, will be elected President.

We have a big country, and different states have different populations, face different challenges, and elect different leaders with different philosophies. Interestingly, as a recent Pew study shows, Democrats and Republicans have markedly different levels of concern about the impact of COVID-19 on health. 85% of Democrats believe the virus is a major threat to public health, while only 46% of Republicans believe this. At the same time, an overwhelming majority of both Democrats and Republicans see the pandemic as a major threat to the U.S. economy (88% of Democrats and 84% of Republicans).

Given the difference between Democratic and Republican states in perceived threat to public health, it is not surprising that states’ responses to the pandemic reflect this difference. Since the initial flare-up, California, New York, and Illinois, for example, have taken a conservative stance toward the virus, locking down their economies early and keeping them locked down for longer. They chose to absorb higher unemployment (California – 14.9% in June, New York – 15.7%, Illinois – 14.6%) in the interest of containing the virus. Texas, Florida, and Arizona, on the other hand, reopened their economies faster, and partly as a result, their June unemployment was significantly lower (Texas – 8.6%, Florida – 10.4%, Arizona – 10.0%).

We calculated the difference in state unemployment rates between January and June for all 50 states and found that states with Democratic governors were willing to absorb 1.7% more unemployment than states with Republican governors. (Excluding two Republican outliers – Massachusetts and New Hampshire – increased the differential to 2.2%.) Twelve of the top 15 states, in terms of differentials, have Democratic governors, including New Jersey, New York, California, Illinois, and Michigan. Do their decisions simply reflect their constituents’ preferences, or are they exploiting the pandemic for political ends? There is no way to know for sure.

What about masks?

With help from the media, the wearing of masks has become a litmus test of “responsible” vs. “irresponsible” responses to the pandemic. There was substantial disagreement early on about the efficacy of wearing masks. The WHO originally said universal mask-wearing was not helpful. (Their website still gives cloth masks only a qualified recommendation if you’re not sick.) The CDC initially took the same stance, although some believe they misled us to try to protect the supply of N95 masks for first responders. Mayor de Blasio of New York famously said they weren’t necessary. Research on their efficacy was equivocal. While N95 masks worn with other protective equipment (shields, suits, etc.) can keep out aerosolized viruses, cloth masks can’t. As one physician put it, “It’s like building a cyclone fence to keep out mosquitos.” But cloth masks do filter out larger particles and droplets, and this appears to reduce the spread of the virus. How much of an effect is still an open question; the science is not ‘settled.’ Health Affairs has a new study out this month suggesting the effect of masks could be significant, and another article forthcoming in the Journal of General Internal Medicine cites cruise ship experience to argue that mask use reduces the “inoculum” (viral load) that exposed people receive, thereby reducing the incidence and severity of the disease.

By now, most Americans seem to believe that wearing masks is the right thing to do in many situations, and about 80% say they “always” or “frequently” wear masks when they are within 6 feet of others. Many large businesses (e.g., Walmart) require customers to wear masks. Will that slow the virus from spreading? As with a lot of other things we are doing – hand-washing, social distancing, etc. – it will probably help. Will it stop the virus? Probably not.

Has the Trump Administration acted responsibly?

As with many things Trump, one needs to separate the administration’s policies and actions from the President’s hyperbolic and sometimes misleading tweets. There is plenty of evidence of uncertainty and learning on the fly in the administration’s response to COVID-19, but little evidence of dishonesty, lack of attention to science, or lack of seriousness of purpose.

If there is dishonesty in this story, it comes from those who are using COVID-19 for political gain. The ‘first place exploitation trophy’ goes to the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives, which blackmailed Republicans in the CARES act negotiations into funding progressive policy goals that had nothing to do with the virus. And they’re exploiting the pandemic to advance even more progressive programs in the $3 trillion Heroes Act. (‘No crisis should go to waste.’) A strong second place goes to teachers unions, which have convinced many affluent school districts and governors that schools should remain in virtual model for the fall, despite: (1) growing scientific evidence that school children are not harmed much by the virus; (2) little evidence that they transmit it to each other or to teachers; and (3) the American Academy of Pediatrics’ express opinion that keeping children home would be more harmful than letting them attend school in person.